Shifting the Burden

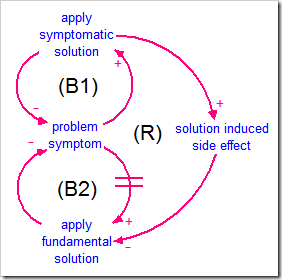

The Shifting the Burden Systems Archetype shows how attacking symptoms, rather than identifying and fixing fundamental problems, can lead to a further dependence on symptomatic solutions. This Systems Archetype was formally identified in Appendix 2 of The Fifth Discipline by Peter Senge (1990). The Causal Loop Diagram (CLD) is shown below.

When a problem symptom appears, two options present themselves: 1) apply a short-term fix to the symptom, or 2) identify and apply a longer-term fix to the fundamental issue. The second option is less attractive because it involves a greater time delay and probably additional cost before the problem symptom is relieved. However, applying a short-term fix, as a result of relieving the problem symptoms sooner, reduces the desire to identify and apply a more permanent fix. Often the short-term fix also induces a secondary unintended side-effect that further undermines any efforts to apply a long-term fix. Note that the short-term fix only relieves the symptoms, it does not fix the problem. Thus, the symptoms will eventually re-appear and have to be addressed again.

Classic examples of shifting the burden include:

- Making up lost time for homework by not sleeping (and then controlling lack of sleep with stimulants)

- Borrowing money to cover uncontrolled spending

- Feeling better through the use of drugs (dependency is the unintended side-effect)

- Taking pain relievers to address chronic pain rather than visiting your doctor to try to address the underlying problem

- Improving current sales by focusing on selling more product to existing customers rather than expanding the customer base

- Improving current sales by cannibalizing future sales through deep discounts

- Firefighting to solve business problems, e.g., slapping a low-quality – and untested – fix onto a product and shipping it out the door to placate a customer

- Repeatedly fixing new problems yourself rather than properly training your staff to fix the problems – this is a special form known as “shifting the burden to the intervener” where you are the intervener who is inadvertently eroding the capabilities and confidence of your staff (the unintended side-effect)

- Outsourcing core business competencies rather than building internal capacity (also shifting the burden to the intervener, in this case, to the outsource provider)

- Implementing government programs that increase the recipient’s dependency on the government, e.g., welfare programs that do not attempt to simultaneously address low unemployment or low wages (also shifting the burden to the intervener, in this case, to the government)

Moving from CLD to Model

The canonical CLD shown above can be confusing in two important ways:

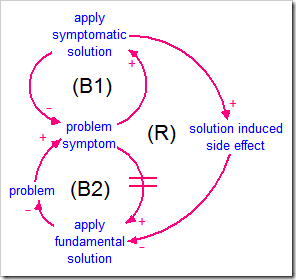

- The problem itself does not explicitly appear in the CLD, but is hidden in the left causal connection of balancing loop B2. In fact, applying the fundamental solution reduces the problem, and therefore the symptom, rather than directly acting on the symptom. In contrast, the symptomatic solution only affects the symptom, so the problem is never addressed and is free to generate more symptoms in the future. This is shown in the revised CLD below.

- The solution-induced side-effect affects the desire or ability to apply the fundamental solution, rather than the actual application of the fundamental solution as implied by the CLD. This works in concert with the delay in balancing loop B2 to inform the decision about which solution to apply.

Even after acknowledging these two issues, the CLD remains difficult to translate into a model. For example, what are the stocks and what are the flows? I intentionally renamed what is normally called “symptomatic solution” and “fundamental solution” to “apply symptomatic solution” and “apply fundamental solution” to clarify these are flows, not stocks. I likewise renamed “side-effect” to “solution-induced side-effect” to emphasize the side-effect was caused by applying the symptomatic solution.

Is the problem a stock or a flow? It could be either, and that will determine whether the problem symptom is based on a stock or a flow. In addition, since the problem is recurring, the fundamental solution will always correct a flow. Finally, since the side-effect is continuously undermining the ability to apply the fundamental solution, i.e., it persists, it must be a stock.

This CLD hides one other detail that makes it hard to model: the causal arrows leaving problem symptom imply a decision point; typically, only one path will be chosen. The decision process is also implied in the CLD, being based on both the solution-induced side-effect and the delay, as well as a perhaps higher cost (not shown), to the fundamental solution.

It is unlikely the decision process will appear in a model constructed from this archetype. When modeling the long-term impact of applying the symptomatic solution, there is no need to include either the fundamental solution or the decision process in the model. In this case, the reinforcing loop R will guarantee the model continues to use the symptomatic solution until the system collapses (the Success to the Successful archetype again). When modeling the long-term benefits to applying the fundamental solution, including short-term use of the symptomatic solution, the decision has also already been made and, again, the decision process remains outside the model.

In the end, I do not believe this is an archetype that is meant to be modeled in its entirety. It allows discussion points to be raised and pieces of it can be seen in models. Recognizing the pattern allows you to change the behavior and escape the potentially devastating results caused by the reinforcing loop. In the following discussion, two models will be presented: one that favors the symptomatic solution and another that favors the fundamental solution. Only the second contains all of the loops in the CLD. Neither one contains the decision process, as the decision was already made based on the purpose of the model.

Exploring Shifting the Burden with Credit Card Debt

People are often tempted to spend more than they earn, ignoring Mr. Macawber’s dire warning in Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield (with updated monetary units): “Annual income $20,000, annual expenditure $19,500, result happiness. Annual income $20,000, annual expenditure $20,500, result misery.” Credit cards, unfortunately, make it very easy to achieve misery and most people do not see the danger of overextending themselves.

Consider someone who takes home $2000/month, but has managed to start spending $3000/month by a sudden change in lifestyle (new house, new car, etc.). This person has $5000 remaining in savings at this point, no outstanding bills or debts, and a number of credit cards with varying limits over $5000. It is clear that within five months, the savings will be used up. What will the person do to cover their expenses? One very common solution, the “symptomatic solution,” is to increase credit card balances by charging more purchases, including the use of credit card checks, and only paying the required minimum payment.

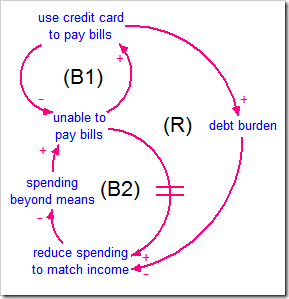

The CLD for this situation matches the Shifting the Burden archetype, as shown below with the symptomatic solution at the top and the fundamental solution at the bottom.

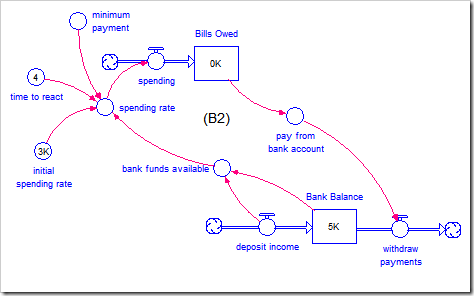

The model below (available by clicking here) implements this structure when the symptomatic solution is always chosen.

The model is divided into three sections, vertically. The bottom section manages a bank account based on income and bill payments. The center section manages spending, accruing bills, and the bill payment process. The top section manages credit card debt (with no limits).

The model is annotated with all constant and initial values. The balancing loop B1 corresponds to applying the symptomatic solution, i.e., drawing on credit to meet payment obligations. The reinforcing loop R corresponds to the unintended side-effects created by this decision, i.e., mounting credit card debt that undermines the ability to apply the fundamental solution of balancing the monthly personal budget. Note that the second balancing loop, B2, which corresponds to applying the fundamental solution does not appear in this model. In fact, with regard to the solving the problem, this model is in open-loop: there is no connection between spending and income (aka the right brain and the left). While, ostensibly, the fundamental solution is to pay the bills from the bank account (there is a minor balancing loop there), there is no ability to do so without first bringing spending into line with income. The real solution to the problem is to either reduce spending (shown in the CLD above), increase income, or do both.

A few assumptions allowed the model structure to be simplified without adversely impacting the outcome:

- The person has enough, or can obtain enough, credit to make it to the end of the simulation. Thus, no credit limits, and no collapse, appear in this model.

- The system is continuous, i.e., there are no monthly payments per se, but payments are made throughout the month as one would expect from a normal stream of bills and a number of different credit cards all with different payment due dates. The implication is that the person in question is faced with the problem symptoms (not enough money to pay their bills), and the choice between the symptomatic and the fundamental solution, on a daily basis.

- While there may be multiple credit cards, only one minimum payment cutoff is modeled. This cutoff should be set to the sum of the minimum payments for all cards being used.

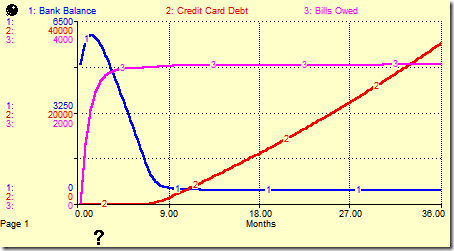

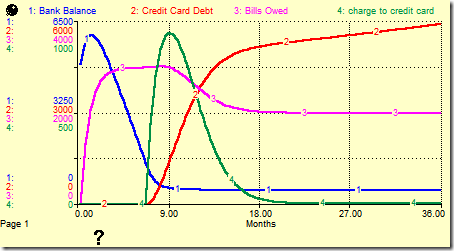

The model simulation produces the following results over three years. Note how quickly the debt runs away, bringing the person to the brink of bankruptcy.

As expected, the bank balance is quickly depleted and the pipeline of bills increases to the monthly spending ($3000 plus the minimum credit card payment). The credit card debt increases exponentially, and has reached over $35,000 after 30 months. The monthly interest on this debt has risen to almost $600, nearly one-third of this person’s monthly income.

Investigating the Fundamental Solution

The fundamental solution (balancing loop B2) can be implemented by restricting the spending – including any credit card payment – based on the money available, as shown below (and available by clicking here). In reality, it will take some time to adjust expenses downward, hence the converter time to react. Note this is the inherent delay associated with applying the fundamental solution. This means that it will still be necessary to borrow from the credit card, i.e., pursue the symptomatic solution in the short term. This is a normal consequence of the Shifting the Burden structure. The maximum credit card balance will then depend on how long it takes to adjust expenses down and how much extra money – beyond the minimum payment – is given to the credit card company. There are, of course, lower interest alternatives to the credit card companies for short-term debt that would make it easier to reduce the debt balance.

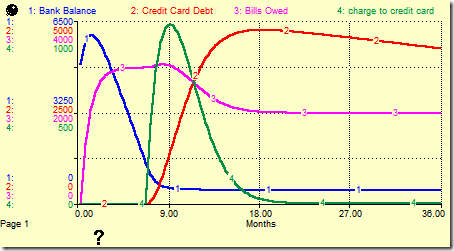

The simulation results for the fundamental solution are shown below. Note the credit card debt continues to grow even after spending has been controlled. This is because the model continues to pay only the minimum payment ($45), which is less than the monthly interest charge (almost $90 by month 36). To reduce the debt (almost $6000), an amount larger than the interest charge must be paid each month.

Forcing the minimum payment to be $100 (by increasing the minimum payment cutoff) is sufficient to both reduce the maximum debt to less than $5000 and to begin to lower the amount of debt.

Summary

Shifting the Burden is an important pattern that helps you recognize when you are caught in a never-ending cycle of applying a symptomatic solution. As the first model shows, this can lead to long-term devastating results. However, it is not true that symptomatic solutions should never be applied. As the second model shows, sometimes they are needed as a short-term transitional fix to stabilize the system and/or buy time until the fundamental solution can be applied. In these cases, a conscious decision has been made to sacrifice some long-term stability (increased debt burden over a long period of time in this case) in order to shore up the system until the long-term solution arrives.